Film screened at UK House of Commons show how a Jewish and a black player broke through the color barrier and anti-Semitism- on the tennis court

Although Angela Buxton applied for membership in the All England Lawn Tennis Club in August 1958, she is still awaiting a reply. Given her tennis bonafides, this may surprise: She reached the singles quarterfinals of the French Open in 1954 and the finals of Wimbledon in 1956. And then, of course, there are those “minor” doubles championships at the French Open and Wimbledon in 1956.

“I think the reason is quite clear,” Buxton says during a conversation in the media dining room of the US Open in New York City. The 80-year-old is reporting for both Florida Tennis magazine, and her native United Kingdom-based tennis publication.

“I can only assume it is because I am a Jew,” she says in her typical feisty style.

Perhaps, but it may also have to do with her doubles partner, African American Althea Gibson at Wimbledon in 1956.

Buxton’s unique life journey began in Liverpool, England in 1934, and has included stops in South Africa, the US, India, and Israel, making her uniquely qualified to break the color barrier in the tennis world.

Buxton’s father, Harry, owned a chain of movie theaters in England. When World War II approached, Harry stayed in England to run the business, but sent his wife, Violet, and two children to South Africa. Buxton fondly recalls her seven years spent in various cities including Johannesburg and Cape Town. She attended a convent school where the nuns and other students — some of whom were Jewish — were very kind.

At eight years old, Buxton began playing in her compulsory daily tennis daily class where she showed great promise.

While the Buxtons were relatively comfortable in South Africa, it was here that Buxton experienced racism for the first time.

“We hadn’t experienced it in England. My mom was no-nonsense when we came across it.” Buxton describes her friendship with a black girl her age, the daughter of servants next door with whom she “played hopscotch and similar games.” Friends and neighbors disapproved of the friendship, noting, “We don’t mix with blacks.”

In a similar incident, the Buxton family was approached by a black young woman looking for some cleaning work. Several days later, she appeared with her six-month-old daughter, desperately seeking a place to stay.

‘You Jews are all the same. You think you own the world!’

“We offered her a job and a place to sleep — on the stoop of our flat” until the landlord threatened to evict them. Despite her mother’s attitude of acceptance, she was also pragmatic and said, “We are guests of the country. We need to keep our heads down and noses clean.”

“This incident stayed in my mind until I met Althea,” says Buxton.

Buxton’s first encounter with anti-Semitism also occurred in South Africa. Her mother Violet was in the common bathroom shared by several flats arranging her hair. When a man asked if she is finished yet, he then remarked, “You Jews are all the same. You think you own the world!” Violet took her comb and hit him. “Twice,” recalls Buxton.

Buxton reflects upon the reason for the man’s comment, and suggests, “There was no good reason — the war was on and Jews were being sent to the slaughter.”

Home again, home again

When the family returned to England in 1946, this time settling in North Wales, Buxton was a true tennis standout.

“I was head and shoulders above the rest. During the war, they had no rackets, no balls and no nets in England. I was beating girls of 18!” Her success in tennis caught the attention of various coaches including George Mulligan, from Liverpool who said of Buxton, “This is a potential Wimbledon champion!”

In 1952, Buxton played in her first Wimbledon in what is known as a “lucky loser” event. She lost in the first round and was very aware aspects of her game were still in need of improvement. Buxton easily convinced her father to finance an extended trip to California. “My father said, ‘Go, take your mother, visit the studios. Tell them you are Harry Buxton’s daughter.’ I even had my picture taken with Doris Day!”

Buxton’s first encounter with anti-Semitism in the tennis world occurred at the Los Angeles Tennis Club in 1952. The Buxtons had a six month lease on an apartment overlooking the courts.

“After two weeks of play there, and after my application for membership was accepted, they gave the money back!” They no longer welcomed Buxton as a member. Buxton matter of factly recalls, “I found out later it was because I was Jewish.”

Buxton turned this rejection into an opportunity; she began playing on the La Cienega public courts. “They were very good courts, and very good people, including Pancho Segura and Pancho Gonzales. They were Mexicans and they couldn’t play at the LA Tennis club either.”

Buxton returned to England in 1953, ready to compete. But after a 6-0, 6-0 loss to reigning Wimbledon champion, Doris Hart at the Bournesmouth Hardcourt Championships, Buxton considered quitting and decided the Maccabiah Games in Israel in October 1953 would be her farewell tennis event.

She traveled with 100 Jewish fellow athletes from England on a ship called “Artza.”

“The journey was awful, but it was fun!” Buxton won two gold medals and returned to England, ready to continue her tennis journey.

Jimmy Jones, a tennis pro and sportswriter coached Buxton, teaching her tactical strategies. She reached the quarterfinals of Wimbledon in 1955.

“Jones always told me, ‘I can help you in the formative years, but you will have obstacles along the way because you are Jewish.’ He wasn’t even Jewish! He was the most influential man in my life,” recalls Buxton fondly.

Enter Althea Gibson

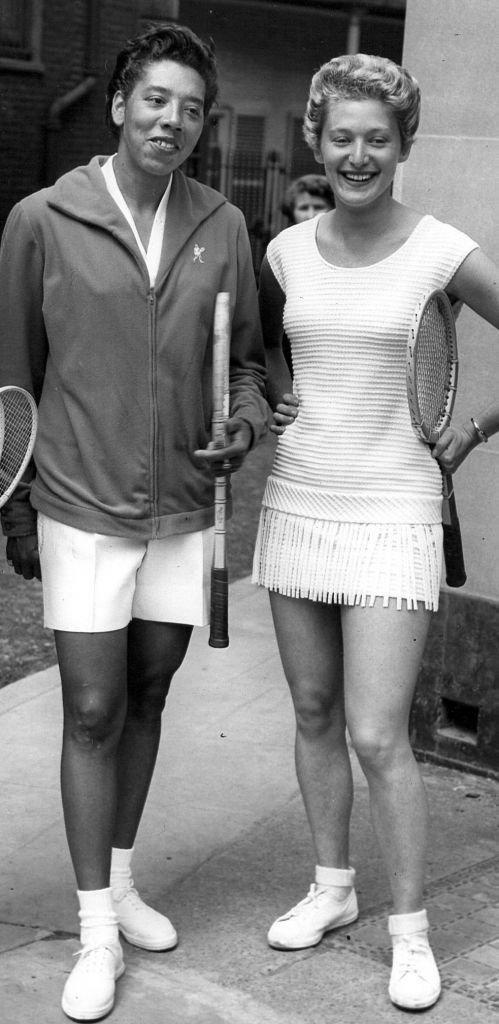

In 1955, Buxton was selected by the government of England to represent her country in a tennis exhibition in India. African American player Althea Gibson was selected by the US State Department to participate in the same United States Lawn Tennis Association-sponsored event. The two women met in India.

The 29-year-old Gibson was born in South Carolina to sharecropper parents and moved to Harlem as a young child. Gibson struggled academically and often skipped school. She spent much of her time playing table tennis and eventually tennis. However, in the 1940s and 50s, most tennis tournaments were closed to African Americans.

In 1951, she became the first African American to play Wimbledon. Later, she would become also the first African American woman to play professional golf.

Becoming a US sports envoy gave Gibson a new entree into previously closed spheres.

“President Eisenhower changed her life. Althea had already hung up her racket and applied to join the army. He knew that sport was a valuable tool to enhance players’ quality of life,” says Buxton of Gibson’s opportunity to travel to India, Pakistan and Burma.

The matchmaker for the successful Gibson-Buxton partnership was Coach Jones. At various tennis events in 1956, he had observed that Gibson was always on her own and not spoken to by other players. He urged Buxton to reach out to Gibson to be her doubles partner at the French Championships and Wimbledon.

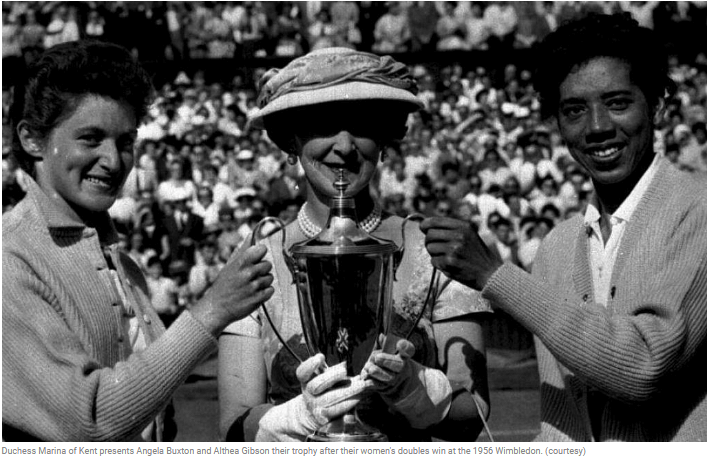

After the pair won Wimbledon, a British newspaper headlined a report, ‘Minorities Win’

Buxton, keenly aware of her own outsider status, approached Gibson, who quickly agreed to the partnership. After the pair won Wimbledon, a British newspaper headlined a report, “Minorities Win.”

Sadly, their tennis partnership came to an abrupt end when Buxton injured her wrist at an August 1956 tennis tournament in New Jersey. While she would persevere and go on to win the Maccabiah title in 1957, soon after she retired from tennis.

Buxton’s colorful post tennis-playing life has included countless adventures in and out of the tennis world, including teaching and coaching tennis, starting the Buxton Tennis Center in north London, sports writing and volunteering on a kibbutz during the Six Day War.

Asked why she journeyed to Israel during this difficult period, she smiles, “I was married at the time to Donald Silk, the president of the Zionist organization of Great Britain and Ireland.”

So Buxton took her three children, 6, 4 and 18 months old, to volunteer on Kibbutz Amiad, “helping in the dining room, the orchards and the laundry.” Buxton recalls, “Damascus overlooked the kibbutz.” Buxton has returned to Israel over the years and is one of the six founders of the Israel Tennis Centers.

Althea Gibson, however, though an American hero who was given a ticker-tape parade after her first Wimbledon win, fell on hard times and was unable to make ends meet. Buxton reached out to many friends and colleagues in the tennis world to raise significant funds intended to help her former partner, whom Buxton describes as poor, ill and considering suicide. Gibson died in 2003.

Buxton’s legacy

Buxton was inducted to the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1981.

Sandra Harwitt, a sportswriter who has covered more than 70 Grand Slam tennis events, includes a chapter about Buxton in her recently published book, “The Greatest Jewish Tennis Players of All Time.”

“Angela lived in a time when women didn’t have a significant voice, yet Angela never held back from offering thoughts and opinions on everything — and pushing for her rights. To this day, she still speaks her minds and has opinions,” says Harwitt.

The active, always on the move Buxton splits her time between England and Florida and proudly reports, “I will be a great grandmother soon!”

Buxton has not yet received membership to the All-England Lawn Tennis Club. But the daughter of a successful British Jewish movie house owner is now herself the subject of a film, “Althea & Angela: A Perfect Match” about tennis and ethnicity, screened before the House of Commons on September 9.

“To be honest, I am a bit in the dark about why they are showing it — and I am going to speak off the cuff,” says Buxton.

(Source: http://www.timesofisrael.com)